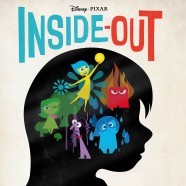

And the Oscar for Best Picture goes to…’Inside Out!’” Pixar/Disney’s delightfully animated movie release, depicting how our brains process emotion. Don’t laugh. Chicago Sun-Times movie critic, Richard Roeper, says, “’Inside Out’ is a bold, gorgeous, sweet, funny, sometimes heartbreakingly sad, candy-colored adventure that deserves an Academy Award nomination for best picture. Not just in the animated category (but) in the big-kid section, right there with the top-tier live-action films. It’s one of the best movies of the year, period.” “Rotten Tomatoes,” the online source devoted to film reviews and news, gives “Inside Out” a 98% positive rating based on the reviews of hundreds of professional critics and publications. All I know is that one month ago, I sat in a movie theatre in front of three people, trying very hard to contain my Glad and Sad emotional responses to “Inside Out” (which are represented in the movie by two of five, main color-coded manifestations). I left the theatre thinking that I had just witnessed an animated, neurological allegory about our emotional brain.

I debated how much of the plot to summarize, but opted for brevity. Here goes.

Riley is a happy-go-lucky girl from Minnesota who is followed throughout the movie by five, basic animations of her emotions: Joy, Sadness, Disgust, Anger, and Fear. Each color-coded manifestation–Joy: Yellow; Sadness: Blue; Disgust: Green; Anger: Red; Fear: Purple–lives in the Headquarters of Riley’s conscious mind. Joy, the principal narrator (the voice of Amy Poehler), works very hard to keep Riley in a happy state; which is not difficult to do in the secure setting of her Minnesota childhood home. All is about to change.

When Riley turns 11 years old, her beloved father takes a new job in San Francisco. Sadness begins tainting some of Riley’s happy memories, which understandably triggers the other basic emotions. Led by Joy and Sadness, an odyssey ensues to restore Riley’s happy equilibrium. Things get worse, much worse, before there’s any sign of improvement. Emotions and memories ebb and flow, and threaten to swallow up the happy-go-lucky girl from Minnesota, who is now distancing from parents, friends, and hobbies.

While Joy has spent most of the movie trying to keep Sadness away from Riley, the denouement of “Inside Out” unfolds when Riley is finally allowed to feel her feelings. What pretention, distraction, compulsion, and suppression were unable to do – empathy and compassion accomplished. Feelings were felt, and memories were modified by Riley’s evolving maturity. The scene with her parents is one of the most moving moments you’ll ever experience. Forgive the hyperbole. This was the moment that I tried my best not to become a blubbering mess. It wouldn’t have mattered because the three people behind me were sniffling loudly.

Hopefully, I’ve encouraged you to see the movie. It’s worth it. It’s entertaining. It’s also informative in how our brains process emotion; an animated, neurological allegory.

Two things. One, the movie depicts the power of empathy to heal hurts and painful memories. In his book Anatomy of the Soul (2010), a book in which Dan Siegel, M.D. pens one of the credits, psychiatrist Curt Thompson, M.D. writes:

“But memory is in fact not like (a safe deposit box). Every time we remember something, the memory changes, for the neural networks that are associated with that mental image are either reinforced to fire in a similar but slightly different fashion, or they are shaped and altered to fire differently. A simple example might help….Perhaps when you were a young girl, your mom reacted with sympathy and warmth whenever you were sad after coming home from school or playing with friends. Each time she responded to you that way, a constellation of neurons was activated, and that network was reinforced and strengthened. You came to expect that your mom would validate you, even when you were unhappy.

If, on the other hand, every time you told your mom you were sad, she looked at you with derision, you felt ashamed as well as sad. Each time the two of you repeated this dance, your memory was strengthened and the association between shame and sadness became stronger.

Even as an adult, then, you are likely to avoid the conscious awareness of sadness at all costs, so that you may avoid the accompanying feeling of shame. This won’t be good for your friendships, marriage, or parenting, as it will be difficult for you to be empathetic with others’ sadness. If, however, you encounter a therapist or a good friend who, when you feel sad, responds with empathy and comfort, your memory of the feeling of sadness will change, even if ever so little at first.

You will not have changed the facts of your past, but you will change your memory of it. You will also change your future because now that you have experienced a different reaction to your sadness, you can anticipate a different response….

Simply put, your right brain, with its nonverbal awareness, can be ‘surprised’ by an encounter with another person’s right brain. If, when you feel sad, you see a look of compassion rather than impatience or disgust, your right brain will register that response as novel and likely respond with a different output of its own.”

This is exactly what happened when Riley’s anger and sadness were met with compassion and empathy. What pretension, distraction, compulsion, and suppression were unable to do, compassion and empathy accomplished.

Secondly, the movie emphasizes the importance of emotions to mental health and well-being. However, an important distinction needs to be made which the movie does not purport to address directly: the difference between “categorical emotion” and “primary emotion.” “Inside Out” emphasizes “categorical” (“basic” or “discrete”) emotion, which is generally what we mean when we talk about emotions; for example, the emotional categories portrayed in the movie, like joy, sadness, anger, and fear. Categorical emotions emerge when we become aware (conscious) of our feelings.

However, “before we are consciously aware of a particular feeling, our bodies have already begun to react,” and that refers to “primary emotion.” The movie implies it, but does not directly intend to address it. Dan Siegel, M.D. does make the distinction between the two kinds of emotion in his book The Developing Mind (2012). So does Curt Thompson in his book. But, I’m partial to a brief explanation from The Emotional Brain (1996) by New York University neuroscientist Joseph LeDoux, PhD. Asking the question “What is an emotion?”, LeDoux references the famous American psychologist-philosopher William James who attempted to answer the question with another question: “Do we run from a bear because we are afraid, or are we afraid because we run?” James proposed that we are afraid because we run. In LeDoux’s words, “The (conscious) aspect of emotion, the feeling, is a slave to its physiology, not vice versa: we do not tremble because we are afraid, or cry because we feel sad; we are afraid because we tremble, and sad because we cry.” Siegel similarly observes that “the body’s response lets us know how we feel.”

Modern neuroscience has helped us to understand that brain time is measured in nanoseconds; that before we become consciously and instantaneously aware of a feeling, the body has already mobilized for a physical response via breathing and heart rates, blood pressure, muscle tone, etcetera. Curt Thompson writes: “This is emotion. The origin of our word ‘emotion’ is grounded in the idea of ‘e-motion,’ or preparing for motion. That is why the phenomenon of emotion is deeply tied to ongoing action or movement. We cannot separate what we feel from what we do.”

Hats off to the movie “Inside Out” and its brilliant depiction of emotion; specifically, “categorical emotion.” But, the implications of “primary emotion?” Well, that might need to be the subject of my next blog?

Bill Bray, Colorado Springs, CO